Tuesday

by Alex Dimitrov

When I can’t talk to anyone1

I like to sit in front of water.2

If I have a minute to feel good3

I take that minute. I have a cigarette.4

I walk into the museum of past lives5

and rearrange all the chairs.6

This poem is meant to be read7

at the bar on a Tuesday8

when you’re dehydrated9

and not feeling so great.10

I want to know you11

like a dog touches the wind12

with its tongue. I want to know13

why time moves impossibly slow14

when pain rises, and what makes it15

speed up like two people16

looking for each other17

at the end of the night.18

When was the last time someone19

looked at you like a bridge20

held by cold air? Like the cars21

flying down the FDR22

taking us where we imagine23

is better than where we are.

I imagined it differently also.24

I imagined more than mixed feelings,

tough leather, the last yes coming25

so quickly. Men and how they

pace awkwardly before parting.26

Cats and how they roam

freely in bodegas at dawn.

The towers in photos.27

The tulips of April.28

The person in a theater

now watching the credits,

reading the names, stalling29

to put on their coat or their scarf 30

or their gloves. Or maybe

not stalling. Maybe they’re

waiting for the music to change.31

Not everything is an ending.32

Not anything’s worth believing.33

And you can begin anytime34

like this whole world began

out of nothing. You can walk out

tonight and feel totally new.35

All you need is the right pair of boots.36

If you know me, you know I’m a great sleeper. As in, I have an otherworldly talent for falling asleep anywhere, anytime, especially if I’m tired—and I sleep monstrously well. But for some reason, I could not sleep last week!! My lack of quality z’s turned into a series of “bleh” days, as my friend L put it. L also—bless her and the ways she knows my heart!—sent me a poem. “No one has touched me for weeks,” it begins.

When my time in Vietnam began, I was given a graph of what my “acculturation” would look like, x-axis time duration, y-axis heart state, aka, a graphical alert that I would indeed feel Sad and Lonely while abroad. I wonder if the graphical down-ticks (of living abroad) have to do with not being touched, and for so long.

My mind wanders, then, to Sylvia Plath, who is famous on Instagram for her journal quote: “I want so obviously, so desperately to be loved, and to be capable of love.”

The other thing Sylvia Plath is famous for is taking her life at thirty. She, like me, was a Fulbrighter. On her grant, she fell in love with Ted Hughes. This man wrote poems about her, married her, had children with her. He also abused her and had an affair with another woman. Sylvia Plath had already been clinically depressed for awhile. I wonder if, as she stuck her head in a London oven—the same one that warmed her pies, and cookies, and other crumbs of domestic bliss—she thought to herself, “No one has touched me for weeks.” It is a very tender, very lonely thing to think to oneself.

Last week, I wrote up a lesson on mental health (it was written in part to my tired, sad self, too). I asked my students, “What are some things you can do to take better care of your mental health?”

One of them wrote this on the board: “Over the heart to someone / allow my seft to rest.”

As I was correcting their answers, I read his misspelled “self” as “soft.” My brain was stumped. My heart, however, was moved. His words were poetry, so I did not correct his (mis)spelling. Instead, when I read his response aloud to the class, I said, “Over the heart to someone, [I] allow my soft/self to rest.”

Two weeks ago, L visited me in my teaching province, and I motorbiked her to the edge of this beautiful river. It was night, which meant the air was full of mosquitoes, and music, and muted sentiment—the kind of night to confess the great secrets of your life. So I confessed.

“I found this river in the middle of heartbreak,” I said. “I cried and journaled a lot here. But now the heartbreak is over, and now I get to share it with you.”

L squeezed my hand and looked at the neon-lit heart sculpture reflecting in the water. “You have your body of water, and I have mine,” she said back. “There’s something about water that moves all of us.”

I ponder very often about water—as a religious, refugee, and literary device. It is a metaphor that ties so many of my identities together, and also many of my loves. I love rain so much I’ll purposefully bike in it. I love the ocean; I love the beach; I love tide pools. I love washing vegetables. I love imagining what it feels like to walk on water. I love, too, Thích Nhất Hạnh’s quote: “The miracle is not to walk on water. The miracle is to walk on the green earth, dwelling in the present moment and feeling truly alive.”

On Wednesday, two of my students took me on a late-snack date night. We drank tea and ate roasted, flavored toast bites. And they motorbiked me to the same river I had motorbiked L. I asked my students (read: friends) if the river had a name. They said yes—Dinh. Dinh, I have since learned, means Peace.

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 1/9/23:] I feel like if my life was a snowglobe and I was a giant looking in, still I would feel such warmth and joy. For so long, I have been writing that I don't want this joy to slip—that I want to hold it, and hold it, and keep on holding it. Even as I traverse the world and back, I feel there is a warmth in my heart that might be likened to the idea of “domestic bliss” —a quiet relationship with the immediate world, which does not ask too much of me, driven by a loving curiosity and grounded by peace and the unshakable faith that the people who love me really truly do love me.

This morning, I woke up in this military hotel room, alone, Billy Joel playing from my laptop, dancing alone in front of the mirror after scavenging for complimentary toothpaste—and as I sit here in this bed, all changed and ready for the day, I think to myself—if nothing in my life changed—if this moment repeated itself over and over again, I would be eternally happy. That is all.

Over FaceTime, G recently showed me the pack of cigarettes some random man put in his hands, which he carried home and stowed away in a drawer. It reminded me of that one time a random man put a stick of Trident gum in my hand, closed my fist over it, and nodded at me, walking away. I never ate that piece of gum, just as G never opened the pack of cigarettes. But G kept his cigarettes, and I kept the gum. I love how people leave little parts of themselves in our lives, like they are Hansel, or Gretel, and cigarettes are their breadcrumbs, and we are their way back home.

This morning, before class, one of my students folded notebook paper into a little box and stuck seven chocolate wafer rolls inside. Then she put it on my desk and said in nervous English, “This is for you.” In that moment, I thought about many things: small kindnesses, origami, and how, as a child, I would pretend-smoke wafer rolls like cigarettes. Mostly, I thought about what is ours and what is not. And I thought of cigarettes again. And then a wafer fell to the floor, and ants swarmed around the broken bits.

So I thought of G, and breadcrumbs, and how we all find our way back home, which is to say, back to each other.

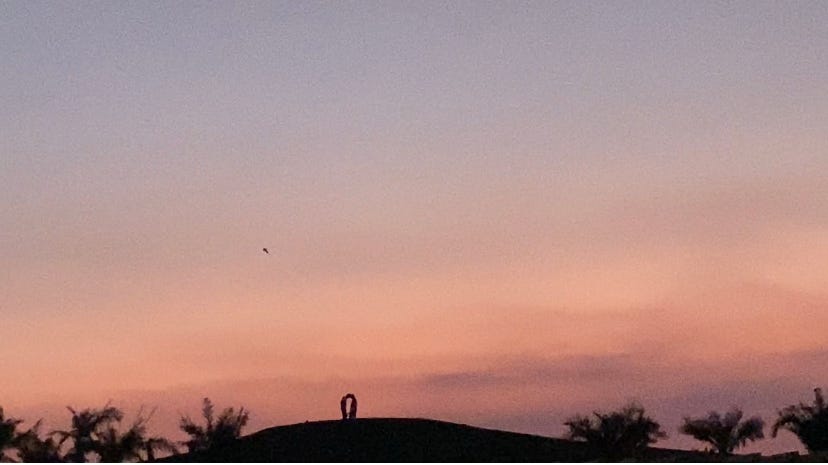

This photograph was taken on November 17, 2022, the day after I had motorbiked myself to Hồ Chí Minh City on impulse without Google Maps and as the sun was setting. It took 4 hours, in between which it poured, I got lost, I asked a guard for help, but he also had no sense of direction, I got lost again, and I had a major life epiphany. See footnote #25 for more. For now: this photograph of the Fine Arts Museum.

I loved capturing this moment—I was witnessing love after love from the window of the museum’s second floor, which overlooked an arch which overlooked the city. If you look closely, you can see three different couples taking photographs of each other, talking to each other, waiting on each other. It reminds me of the poem “Credo” by Matthew Rohrer: “I believe there is something else // entirely going on but no single / person can ever know it, / so we fall in love.”

During my stay in Vietnam, three main chair motifs have surfaced: (1) steel stools, (2) red/blue plastic stools, and (3) wooden chairs. The first two are my regular companions at street eateries. Shops with steel stools are a little pricier, and in their presence, I often venture to ask for trà tắc or soda chanh. If you’re in the presence of the red/blue plastic stool, however, you know you have found yourself a proper street vendor—the closer to the ground the stool is, oftentimes the better. At these shops, iced tea is the way to go. Your eatery is also probably not findable on Google Maps, or, if it is, there are few pictures to prove its existence. But it exists alright. And the food slaps. And the restaurant is also a home. And you will want to come back.

Chair #3, the Wooden Chair, is ever-present in my professional life, i.e., that of a teacher. Classrooms in Vietnam are furnished with long wooden tables, three wooden chairs to each. It’s hard to spice up learning activities because of this hardwood set-up, but still I try my best. Once, I stood up on a wooden chair and said something opinionated, and the students gasped, and I felt like Robin Williams in Dead Poet’s Society.

In an interview with NPR, Mary Oliver said, “One thing I do know is that poetry, to be understood, must be clear. It mustn't be fancy.” (In a nod to footnote #6, Mary Oliver also said in this interview that the two things she was enamored by as a child were (1) the natural world and (2) dead poets, who were her “pals.”)

In an essay for Poets & Writers, Alex Dimitrov reflects on the making of his poem, “Love”: “I kept the form and the language accessible because it was important to me that any person, even one who didn’t read or like poetry, might enjoy and understand the poem, should they encounter it online. And I wanted the poem to be encountered… I hoped people could see themselves in some line or some future line I hadn’t yet written.” Alex Dimitrov is, of course, the author of the poem that makes up this blog post.

In her recent substack post, Tara Monjazeb wrote that “reading a poem is a form of self-intimacy.” She quotes Jeanette Winterson, reminding us that poetry is “not a hiding place, but a finding place.”

Here is a picture of that one time I was so stressed out about meeting the freshman class that I forgot my water bottle at the local park and left it there for a day and a half.

You’ll see it’s at the edge of a lotus pond because I’ve taken to dusk-time meditations here (usually after a run).

This BPA-free Nalgene gem had been hand-delivered by C when she came to visit me in February (I couldn’t find any large BPA-free water bottles in Vietnam and had been dehydrated for several months). The truth is that my mom had sent me the same exact Nalgene before, but I had lost it on a chaotic bus ride to Sài gòn. I moped for about a week.

Anyways, thank you again, C. And—sorry again, Mom.

Last week, as noted in footnote #1, has been sullied by insomnia. In other words, I have been feeling Not So Great. On Thursday, wearied out of my very bones—coping via brown sugar boba, some seasoned fries, and a rerun of Everything, Everywhere, All at Once—I received a text from one of my students.

“Hi kaitlan you seem tired, hope you will sleep well tonight and tomorrow good things will come to you P/s:my grammar is not very good ,I hope you can understand.”

Oh, how my heart swelled! I called my mom and read the text aloud. I screenshotted it and sent it to A. I hearted my students’ message 7 times. I said thank you. I thought about what Marie Howe once said—that “the moral life is lived out in what we say more often than what we do.” And the next day, like magic, was an occasion for joy.

There are several ways I want to know you, and several ways I think we can achieve that. For example, we could, together: read on a train, steal motel soap, and/or watch snow. I want to know you without stopping myself just because I fear we might feel / embarrassed or impractical, or get wet.

I ran into my student, L, after class at my favorite fried rice/noodle place. Turns out that it’s also L’s favorite place! (IMHO it deserves to be many people’s favorite place.) Both L and I had been planning to order take-out and eat by ourselves, but then the opportunity arose to eat together! And so we ate. Up until that point, I had been having a “bleh” day. Sharing this meal with L made it so much more than “bleh.”

Then! To top it all off, this little dog meandered over and found shelter under my legs! Then he smiled at me!

L and I ate together again today. We decided it’d be a Thursday ritual.

I’ve been thinking a lot about language, and especially what it means to slip in and out of Vietnamese (what I consider my mother tongue) and English (what I consider my native tongue).

“I know a lot more Vietnamese now,” I bragged to my mom over the phone. But what does it mean to know? And does it mean to know “more” via language?

When it comes to speaking, I think about power (the intimacy of Vietnamese pronouns, the intimidating force of English, etc.). When it comes to writing, I think about representation (what is the function of italics, how do we write in resistance, etc.). I think, also, about Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s warning that “the right to conquer is intimately connected to a right to know.” I wrote about the violence of knowing before. Now, I am asking: what does it mean to know through words, through language, and then to contribute to others’ knowing?

In my search for answers, I have stumbled upon a poem, a personal essay, a craft essay, and a video.

Yesterday, I also began reading Javier Zamora’s Solito. I was struck by his brilliant ¡use of punctuation! and was curious what others thought of it. The first review I found (on Goodreads) began, “So you should read this if you want to know a real migrant story.” The user—a certain Kate O’Shea—repeats this idea of “real migrant story,” praising Solito’s authenticity, musing, “It certainly makes you realize how afraid and desperate people have to be to undertake this journey.” And then she repeats: “Highly recommended for anyone who wishes to read a real migrant story.” But what is a real migrant story, anyway? And who are we to measure desperation?

I was appalled by Kate’s review. In my horror, I recalled how G once phrased this kind of entitled, glutinous reaction as “eating culture.”

Every time I think of what G said, I also think of a poem: “Simone Weil says that when you really love you are able to look at / someone you want to eat and not eat them.” I also think of Claudia Rankine/Beth Loffreda’s foreword to The Racial Imaginary. They write, “To say this book by a writer of color is great because it transcends its particularity to say something ‘human’ (and we’ve all read that review, maybe even written it ourselves) is to reveal the racist underpinning quite clearly: such a claim begins from the stance that people of color are not human, only achieve the human in certain circumstances.” They speak directly to readers like Kate O’Shea, whose book reviews are definitively not loving.

Plenty of research and literary categorizations are not loving. Eating someone is not loving. Eating someone’s culture—someone’s story—wanting to know them without first examining oneself (of one’s own privilege, power, and tendency to Other)—is not loving. Recommending “real migrant stories” not only misses the point and ¡brilliance! of authors of color. All these ways of “processing” the Other are not only lazy and unkind but also unloving.

Over the years, I have often returned to Amit Majmudar’s NYT Opinion piece, “Am I an ‘Immigrant Writer’?” Amit begins, “I learned recently, to my surprise, that I had written a novel about the immigrant experience. The novel I thought I’d written was simply about a mother and daughter, but the inside flap of the book jacket made it clear I had ‘written anew the immigrant experience.’” I return to Amit’s words whenever I feel dissatisfied and uncomfortable with the fact I studied “English” in college. I return to it when I feel dissatisfied and uncomfortable with the fact I’m teaching English in Vietnam on a fancy Fulbright grant funded by the American government. I return to it when I feel dissatisfied and uncomfortable with the fact my native “English-language-ness” is so desirable, so powerful, and, yes, so expensive, especially here in Vietnam.

As a writer of color, a woman, a poet—no, scrap this categorizations, I mean: a human!—I often dream about what it means to rewrite the English language. I want to “creat[e] the world in my own image. / Mine will be a gentler, more womanly way / To describe my progress.” I often wonder to myself, if I were to publish a book tomorrow, how would it be categorized? Surely not as “English literature.” But in equal-opposite fashion, I hope it wouldn’t be categorized as “(im)migrant writing,” either. So where on earth do we go from here?

In recent weeks, I have returned to R.F. Kuang’s recent review of Everything, Everywhere, All at Once. My favorite section reads, “... a friend seeking reading recommendations recently told me she was tired of reading the Amy Tans and Maxine Hong Kingstons of the Asian American literary canon because she was tired of being reminded constantly that she wasn’t from here. “God,” she said, “I want to read Asian American writers talking about something other than how they don’t speak good Chinese and don’t get along with their parents.” This sentiment doesn’t disparage all the necessary and important works that have to date defined the canon. But it expresses a desire—fairly widespread, I think—to find creative identity in more than just non-belonging. What happens next?” I fully believe the entire point of literature is to imagine those potential futures. I love thinking about the ethics of that process, and employing methodologies of care in my own writing process.

In other words, I love thinking about what it means to complexify the notion of certain “literatures.” What does it mean to:

“I picture a border between fiction and nonfiction, and I am making that border very wide.” –Maxine Hong Kingston

“The more languages you speak, the closer you are to truth.” –Haoran Tong

follow a ripple of consequences—to paint a portrait of wholeness?

“When I look at the ripple consequences of decisions over the years, it’s really interesting to see how a life can take a particular path and not another.” –Laili Lalami

“Writing could be said to rest on the faith that there is something of value in witnessing an individual mind speaking in and to its ordinary history.” –Claudia Rankine

translate without re-enacting violence?

“An act of translation is always an act of betrayal.” –R.F. Kuang

“... the joy of moving words from one language to another… so that readers… might have a relationship with [the story].” –Jhumpa Lahiri

“If we have to use someone else’s words, let us, at the very least, not delude ourselves into thinking that they are our own. Let us, at the very least, try to turn the involuntary process of language into a deliberate act.” –Benjamin Moser

co-exist and thus speak (joyfully) from the (creative) margins (as a site of resistance)?

“Coexistence should not be a passive state… Coexistence, rather, should be the active practice of becoming familiar… with people who are different.” –Laila Lalami

“I think it’s an act of care to write a book like this. It’s an act of love to write a book that is critical…” –Laila Lalami

“This is where refugee aesthetics come into play because the potent forms of desire, play, and beauty found in art give subjective agency to the artist, which cannot be reduced to the ideal singularity of citizenship, law, economics, identity, or politics.” –Long Bui

“If she could feel deeply, she could be free. She knew that beauty was not a luxury, but like food and water, a requirement for living.” –Saidaya Hartman

“My work: to imagine… My work: to do more than reproduce the toxic stories I inherited and learned. In / other words: just because it is art doesn’t mean it is inherently nonviolent. My work: to write poems / that make people feel seen, safe, or otherwise loved.” –José Olivarez

“I am speaking from a place in the margins where I am different—where I see things differently… This is an intervention. A message from that space in the margin that is a site of creativity and power, that inclusive space where we recover ourselves, where we move in solidarity to erase the category colonized/colonizer. Marginality as a site of resistance. Enter that space. Let us meet there. Enter that space. We greet you as liberators.” –bell hooks

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 10/9/22:] It is October already. I’m in Vietnam. I still find that incredible, unbelievable—and when I think about it for too long, it becomes overwhelming. There’s this constant question in my head: will I survive? Sometimes even just the concept of getting through it is difficult. Time passes differently here…

The park which I frequent—I can bear no more than two days without visiting—closes every day at 9 p.m. One of my favorite things to do is to arrive just as the sun is setting, and then to stay until light has long left the sky. Around 5, the park is full of families flying kites. Around 6, they begin to leave. Around 7, the park clears up. Around 8 and then into 9, the park is full of young couples hiding in the darkest corners. They are leaning into each other, falling into each other, falling, yes, I do believe, into a greater love. Every time I allow myself to stay a little later and walk the park late at night, I think of Dorrianne Laux’s poem, “Kissing,” which literally begins, “They are kissing, on a park bench.” Later, she writes, “I want to believe / they are kissing to save the world, / but they’re not. All they know is this press and need…they are doing what they have to do / to survive the worst, they are sealing / the hard words in, they are dying / for our sins. In a broken world they are / practicing this simple and singular act / to perfection. They are holding / onto each other. They are kissing.”

I’ve never stayed in the park past 9. But I know they have.

…hugged you? I find myself counting the weeks in between every time I am hugged—a function, I think, of living abroad (see footnote #1). Currently: 2 weeks and 4 days.

Providence, Rhode Island, is home to both my alma mater and one of my favorite places in the world: Pedestrian Bridge. If you talk to me, you know I like to talk about Pedestrian Bridge all the time. All the time! In my last year of college, I would walk to Pedestrian Bridge, I would go on runs and end my route at Pedestrian Bridge. I would eat there; I would cry there; I would invite friends there and talk about faith and ice cream and the stuffy erudition of—ick! but also wow!—academia.

When I first arrived in my teaching province and was hit with living-abroad loneliness, S would send me picture updates of Pedestrian Bridge. And about two weeks ago, S sent me another update:

I forgot to tell you I bought a motorbike. It’s like my Pokemon. I named it Clifford. Notice I have not given it any pronouns because I hate how people (often men!) name their luxury transportation goods feminine names. It’s totally gross. But I like “Clifford” because it reminds me of my childhood, and Clifford was big and friendly and not-sexist, and he would happily (and safely) take Emily everywhere. Anyways, here is a picture Clifford right after my purchase (The bike next to Clifford was also mine, gifted by my school. It has since been stolen):

We’ve been through A Lot together, like almost dying at 10 p.m. in the middle of nowhere and then almost running over a kid on a bike. The first was my fault; the latter, not so much. I promise I’m a good driver. Come to Vietnam and see for yourself.

There is neither FDR or PCH over here in Vietnam. There is, however, the big street I drive on almost every day, Cách Mạng Tháng 8 (whose, for the purposes of this blog post, I finally took the time to consider: “August Revolution”). I drive down this street to get spicy Korean-style noodles, chè, bún bò, sushi, coffee—as well as to buy my groceries, baked goods, and to pick up anyone who comes to visit me.

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 3/29/23:] Imagine: a good thing that stays.

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 11/9/22:] Sometimes I feel like I am very strong and doing well. Sometimes I feel incredibly weak. Right now I am flipping in the middle of both, and the flipping hurts, and I wish my brain could just stop turning in circles. Suddenly, I had this thought, which is: there is so much left of this journal. And I wonder, by the end of it, when I reach the last page, where my heart will finally be.

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 2/16/22—the last entry of that journal:] I’m currently in the middle of watching Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and in it, Jim Carrey’s character says, bundled up and lying on the ice with his lover, something like: “I’m just so happy. I’ve never felt this way before: so happy with this exact, particular moment.” Here’s the thing: I feel the same exact way.

Maybe this is the feeling when you have sat with the weight of eternity, understood deep in your bones—through grief and desperation but also, yes, joy—that eternity is simply the infinitude of the present moment, as it melts into another and another and another. That it is nugget after nugget of glowing joy.

And so here we are, approaching the end of this journal and stepping into a new beginning. Piano music is playing, the pilot is speaking to us over the intercom. Higher and higher I am flying into a life just beyond the moon, and, as Mary Oliver said, still I cannot find a perfect place. So I will just say it now, on seat 26F, into the Vietnam sky, which is to say the infinite sky of this beautiful earth: “Thank you, thank you.”

During L’s visit, she asked me if I had any particular hopes for my last 2 months of my teaching. (We were seated across from each other in the coffee shop I now write to you from.) After about an hour of consideration, I told her I only really wanted one thing: to feel good about all my last yesses.

“When I almost died riding my motorbike to Hồ Chí Minh City,” I told L, “I realized something very obvious but also kind of profound. Which is: this is my life. And I can do anything I want—anything! And that is a miracle!”

The “officially” published version of Alex Dimitrov’s poem, “Love,” ends with this line: “I love anyone who cannot say goodbye.” Alex is still (“unofficially”) writing the poem today.

Photographs of towers in Saigon, Singapore, and Thailand, respectively and in chronological order. These photographs were taken with my (new, overpriced) film camera, which I proceeded to break (and whose film I proceeded to burn/rip, as well). I made a friend in Sài gòn, who fixed my film camera. I call him “uncle” and I have his number saved. Unfortunately, a different part of my camera broke recently. I may need to return to the city and ask for his help again. Beware film cameras! They are fragile, albeit precious, things!

It is April already! My Fulbright grant is over in less than two months! (And, in a very literary way, the first day of our final meeting is exactly one year from my college graduation: May 29, 2023.)

Of spring (and/or April), poet Kim Addonizio writes, “it’s starting again, the longing that begins, and begins, and begins.”

“For M” by Mikko Harvey is, perhaps, the only poem that has ever made me cry. He writes one of the most tender lines about what it means to stall, to wait, to wish: “Please linger / near the / door uncomfortably / instead of / just leaving.”

The next several lines of “For M” read, “Please forget / your scarf / in my / life and / come back / later for / it.”

Okay, brief intermission from the Main Content to say: I think I have been way too over-over-over-overzealous with this blog post idea. I’m sitting in this cafe for the second day now, writing. This morning, the music began with Charlie Puth. At some point it slid into Bill Withers. Currently, we are weathering a strange jazz/lofi/classical mix. I am not too sure I am fond of said mix, or maybe I am just not fond of typing in footnote-size font! The sun is also setting! Imagine how long I have been sitting here!

A recommendation: don’t footnote every line of a poem! Unless you want pins and needles in your legs, and bad flashbacks to thesis-procrastinating days, and bad jazz/lofi/classical music. (I’m not even joking, a roboticized voice is singing “que sera sera” ten times over.) Tap out! Tap out!

(P.S. I have decided, perhaps to your relief, that I will not footnote all 47 lines of this poem.)

Evelyn: Maybe it's like you said. Maybe there is something out there, some new discovery that will make us feel like even smaller pieces of shit. Something that explains why you still went looking for me through all of this noise. And why, no matter what, I still want to be here with you. I will always, always, want to be here with you.

[Joy starts crying]

Joy: So what? You're just gonna ignore everything else? You could be anything, anywhere. Why not go somewhere where your daughter is more than just this? Here, all we get are a few specks of time where any of this actually makes any sense.

Evelyn: Then I will cherish these few specks of time.

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 11/9/22:] The truth is, there is so much in my life that I am not noticing. The truth is, I can do anything I want and go anywhere I want, and I have already, and I am, and I will. And the truth is, every day is wonderful and beautiful and even if mundane, rich and full of the greatest flavors there ever were. And I want to breathe joy and life and love into this world with every precious breath that I do have. And I want to hold these memories dear to my heart and the people in my life whose presence I don’t know how long I’ll be able to keep—even dearer. I want to love and live wildly with every ounce of human inside of me. I want my writing to drip with the honey of that joy and wonder.

“So I imagine / such love of the world—its fervency, its shining, its / innocence and hunger to give of itself—I imagine / this is how it began.” –Mary Oliver, “Of Love”

[Excerpt from a journal entry on 3/29/23:] Oh, it feels so wonderful to walk in this world right now, a universe unto myself.

Today, I am wearing the same pair of shoes I wore the first day I wrote to you. Please write back to me! I miss you, and I still cannot wait to hug you.